It is no longer a matter of debate that human activity is changing the environment and the course of the climate (IPCC 2022). To be more precise: it is no longer a matter of debate that capitalism is intrinsically linked to this change (Klein 2015; Moore 2017). (Eco)feminists would go even further to say: it is no longer a matter of debate that our current patriarchal capitalist society is at fault for the multiple social, environmental, and climatic crises and that these crises are related; they are all the outcome of a society that is built upon the ideologies of oppression (e.g. exploitation, violence) and domination (Mies and Shiva 1993) – ideologies that affect human and non-human nature alike. What is more, it is no longer a matter of debate that these ideologies manifest in and shape (urban) space (Lefebvre 1991); as Christine Bauhardt (1997) once put it, “the current organisation of (urban) space reflects the social organisation of an unjust society”.

Eradicating these ideologies is at the heart of (eco)feminist critique. To hooks, feminism is “a struggle to end sexist oppression” and, therefore, “necessarily a struggle to eradicate the ideology of domination that permeates Western culture on various levels, as well as a commitment to reorganising society so that the self-development of people can take precedence over imperialism, economic expansion, and material desires” (hooks 2015). If the way we organise society is reflected in (urban) space, how, then, would a world that takes feminist concerns and perspectives seriously look like?

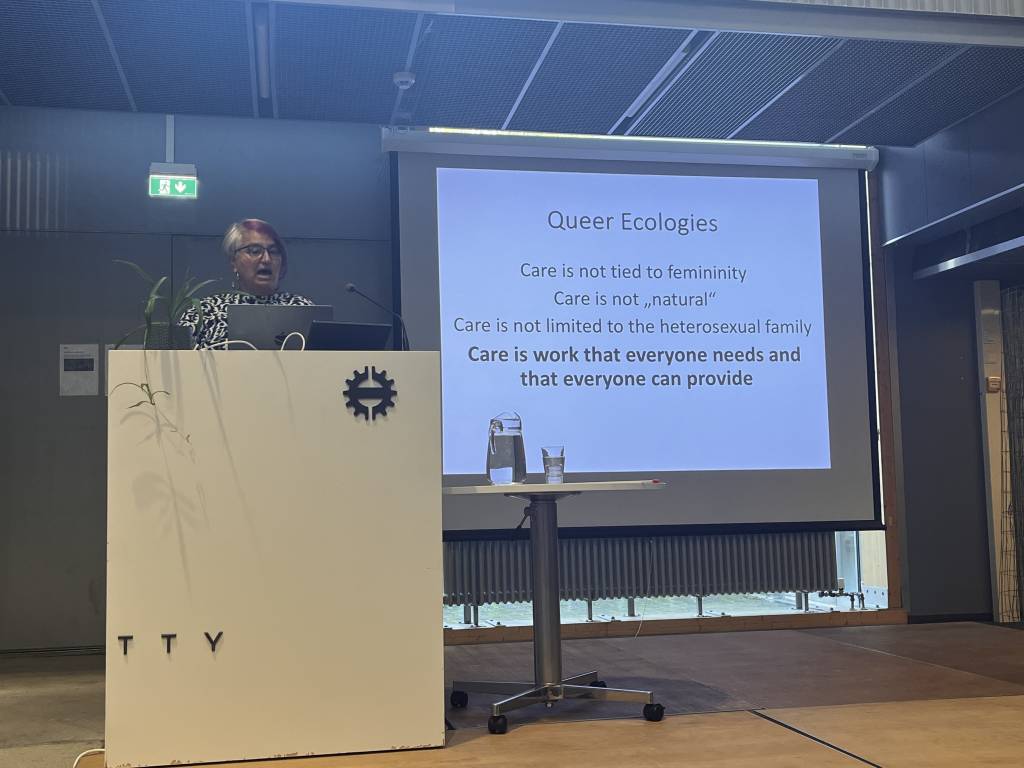

To explore this question, we organized a three-day event comprised of keynote lectures followed by a hands-on workshop. The aim of the event was to learn about (eco)feminist theory and to explore how through feminist critique a more just and sustainable world could be imagined. Setting the stage, Prof. Christine Bauhardt imparted the first lecture entitled “Feminist approaches to socio-ecological transformations”. Here we were introduced to ecofeminist theory and the concepts of social reproduction and care, both of which are at the heart of feminist critique albeit grounded on different philosophical underpinnings (Bauhardt 2019; Fraser 2016; 1985) and which feminists argue are in crisis under capitalism despite being essential to human existence. Then, we learned about three different perspectives of how a non-capitalist society could be organised – European Green New Deal, Degrowth, Solidarity Economy – analysed through a feminist lens and how these deal with matters of social reproduction and care. This lecture elucidated how even these apparently progressive alternatives to capitalism continue to create gender binaries that still represent care work as “women’s work”. On the second day, we were joined by architect and Prof. Frances Holliss who presented her research on the “Workhome” and illustrated how, the separation between work and home, was intrinsically gendered and rendered invisible the multiplicity of work undertaken at home. Her lecture well showed how the organisation of a capitalist and patriarchal society affected the organisation of urban space as well as the organisation of spaces within the home. Holliss’ lecture was followed by Bauhardt, who presented Queer Ecologies, a strand of ecofeminism, and how this theoretical framework can help defeminise care work to begin to think of truly just and sustainable futures. Following their respective lectures, Bauhardt and Holliss sat together and discussed their imagined feminist future worlds. The third session kicked off with a hands-on workshop in which participants were asked to produce a 10-minute podcast and a drawing discussing and portraying their feminist worlds.

I first encountered the work of Christine Bauhardt in mid-2023 while I was listening to the “Lila Podcast: Feminismus für Alle”. The episode was entitled “Wer had, dem wird gegeben – Feministische Kapitalismus-Kritik mit Marlene Engelhorn and Christine Bauhardt”, shortly translated, feminist critique of capitalism with Engelhorn and Bauhardt. I have been following this podcast for several years and particularly one episode inspired me to think about a world not only as seen/scrutinized through a feminist lens, as most of the podcast does, but created through a feminist perspective. The episode was entitled “A feminist world – unsere feministischen Utopien und Träume” (A feminist world – our feminist utopias and dreams). Through their feminist lenses, the hosts of the podcast discussed exactly what their feminist utopias would look like, and how they shaped spaces, cities, and policies. This episode served as the basis of the hands-on workshop in which we asked participants to create a 10-minute podcast accompanied by an illustration addressing the following question:

Imagine a world that takes feminist concerns and perspectives seriously; concerns where justice, care, and love for all sorts of life and the environments in which these unfold are at the centre:

What would that world look like?

How would cities and homes be like?

What kind of living environments would be constructed…

…and how?

In what follows, we present a selection of these podcasts: From (eco)feminist theory to restorative spatial practices.

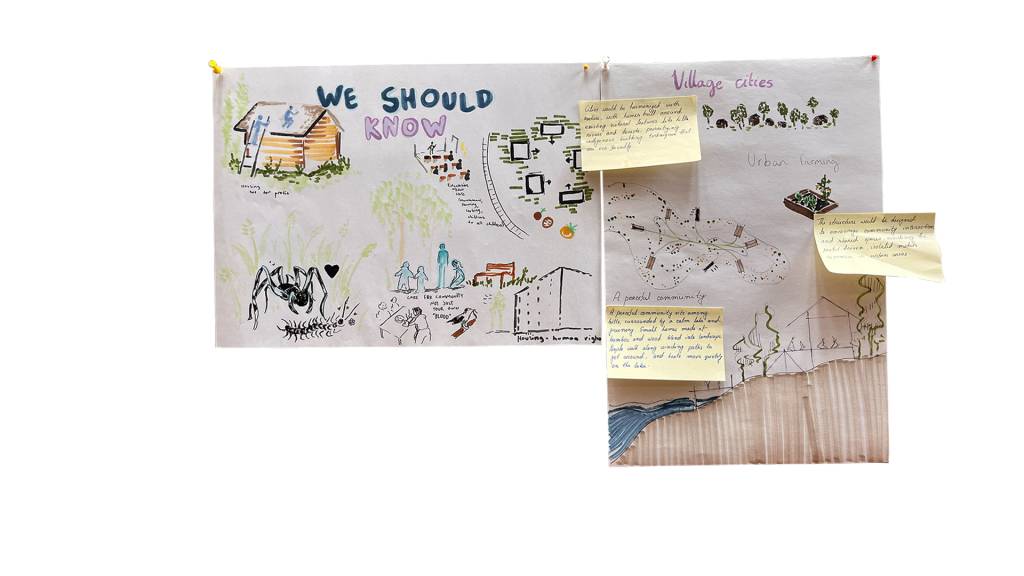

“So I imagined a community where people live simply connected to nature, without modern technology, capitalism or profit, rather guided by cooperation, care, and sustainability… A peaceful community sits among hills surrounded by a calm lake and greenery… Cities would be harmonised with nature.”

“I imagine a place where there is no greed, which I think is behind every big development and corporation. In this utopia there is no greed, there are no big cities.”

“There would be less transportation, less pollution, less consuming”

Listen the podcast: We should know.

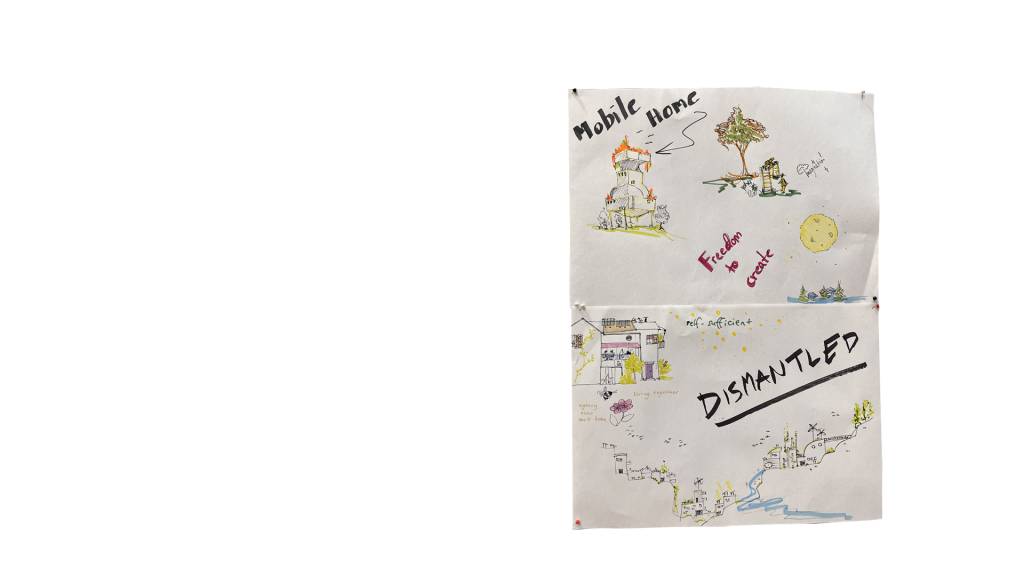

“The podcast is titled dismantled… thinking of how to rid ourselves from authoritarian powers… I had a picture in my mind of a community that lives with its own rules and, somehow, builds their houses autonomously… only building what is needed.”

“Yes. We should strive for more ground-up living, building environments that everyone can equally participate in…a different kind of power”

Listen the podcast: Dismantled.

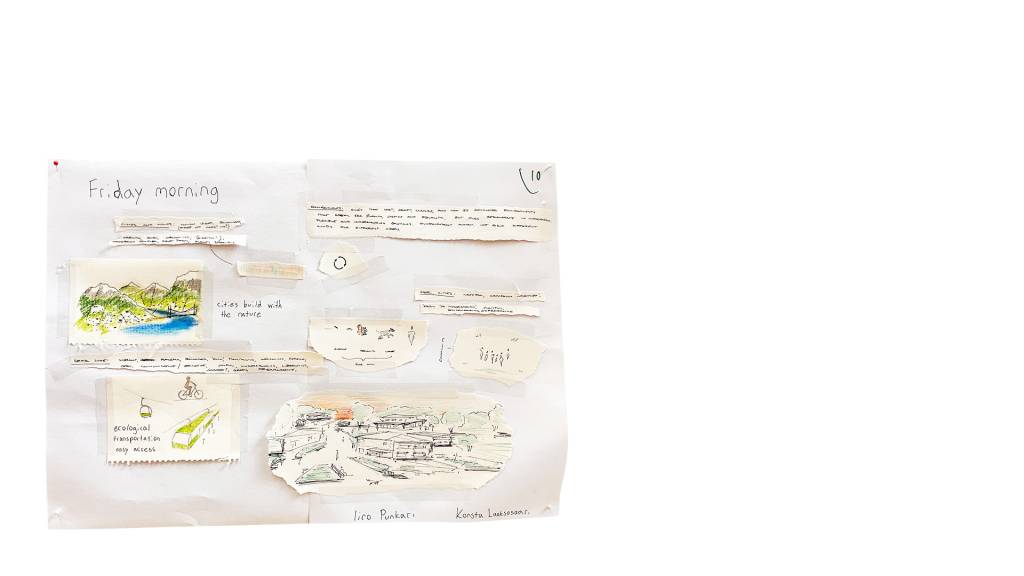

“I think cities should be human-sized… smaller communities. Cities would be balanced, even welcoming, maybe even earthy. Kind of like naturally complex, so that they have formed in a natural way. A free form.”

“Yeah. The earthy part is like, yeah, because we want equality for people, of course, but also for nature. So for all animals and whole ecosystems. Yep: equality and justice.”

“Home would be human-sized, peaceful, vibrant, balanced, and functioning in all these senses.”

“Yeah. And everyone would have a house. It would be really great.”

Listen the podcast: Friday Morning.

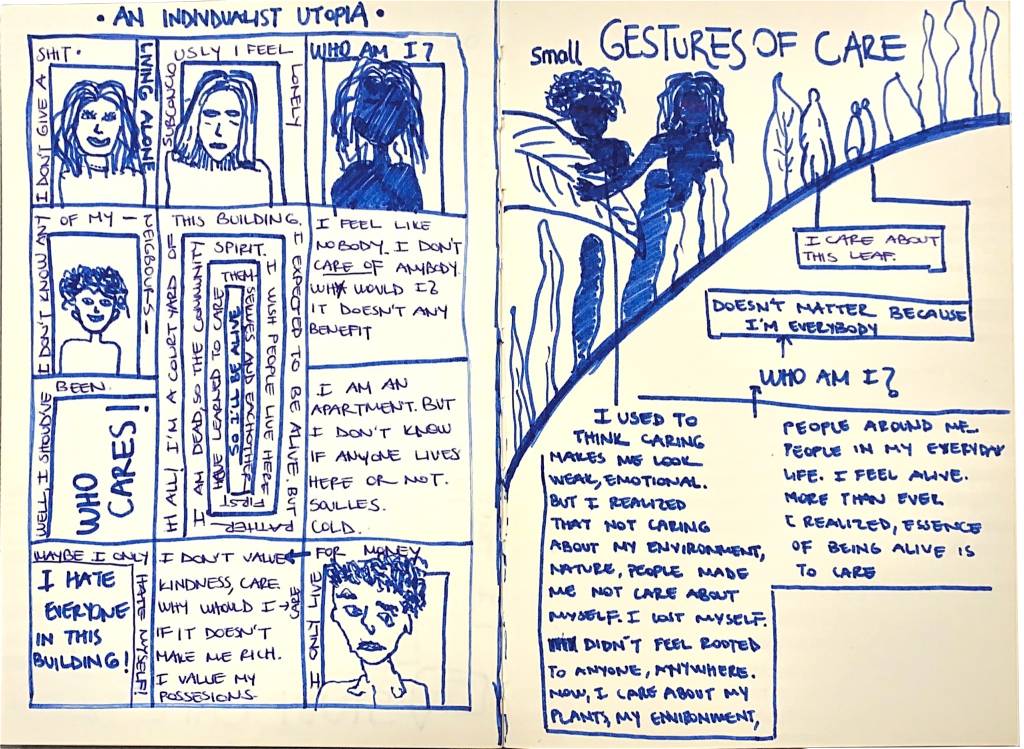

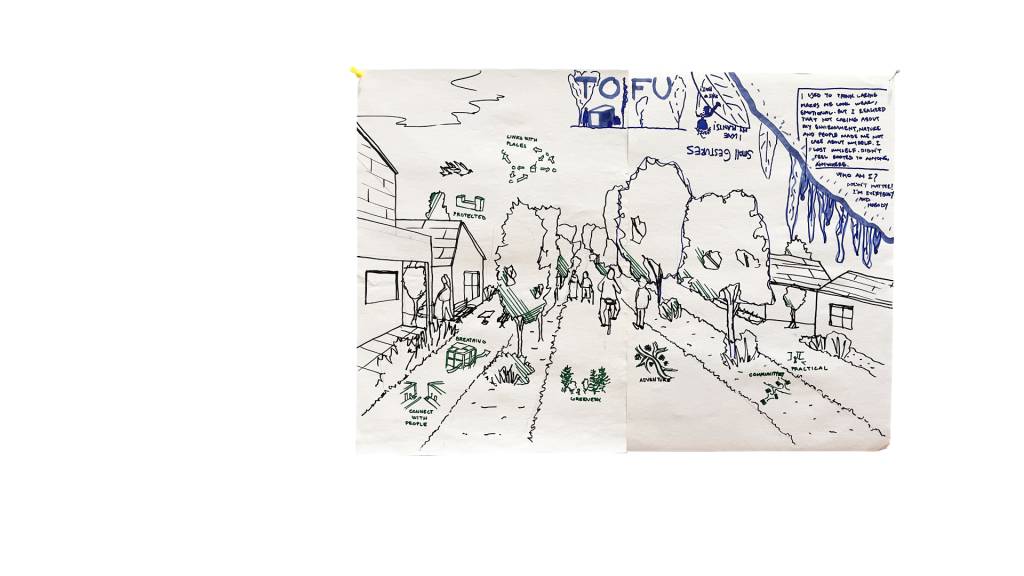

“I am Spoiled Child. I named myself like that because I want to really spoil my inner child with the feminist city.”

“I am Papagai because I was thinking of a birdie view and it reminded me of the 15-minute city, a good starting point.”

“I am Black. I called myself like that because it’s like the one odd one in the community sometimes, and I was thinking about alternatives to commercial living models, like intergenerational living or farming communities or like eco-villages even.”

Listen to the podcast: Fairytopia.

“I think that we can narrow it down to some adjectives and some characteristics that this utopia could have. Things like being inclusive, like diverse, and just focusing on care. Also work, but we also have to specifically say how these things can happen. Like in my opinion, an ecofeminist utopia is a city or a community which has really pedestrian friendly connections and its emphasis is on public transportation instead of cars and using. Energy-consuming ways of transportation. And the resources that people use in the community are shared and not really individually divided and, because these communities are focused on care, care centres for children and the elderly should also be combined in the city and the community so people can take care of themselves and grow together and help each other.”

“Then we can expand the practice of care into our daily lives, like on a bigger scale, like we can care about other people, ourselves, our plants. And I think that this approach is beneficial. To create an approach to care like, I think that it’s a muscle, so we should start developing it with really small steps.

Listen to the podcast: TOFU.

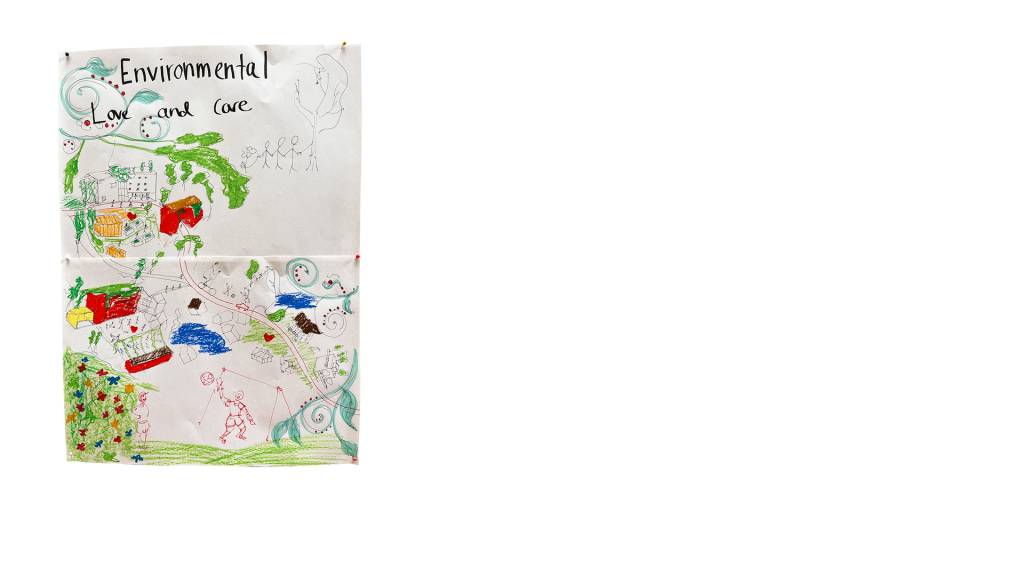

“Welcome to the Environmental Love and Care podcast. My name is Care and I am here with Love. Love, do you have some thoughts about ecofeminism?

Love: Yes. I think ecofeminism means there is space for different people, nature, mixed functions in the city…

Care: And that they work together.

Love: Yeah. And people have a community and meet and care for each other.

Care: And that we have shared space for them.

Love: Yeah. That there is space for children can move around without cars.

Care: Like safety. So, you imagine an open space where all can be?

Love: Yeah. And feel safe and nature can be a little wilder.

Care: Like without visible borders? Yes. Amazing thoughts.

Love: Maybe local production.

Care: It is very important what you say about shared space. I think it can show cultural difference, for example, in a library or in city malls or something like that or museums, different people with different culture… This shared space, it actually works and it’s open for all people and I think that it can be like an indicator about such kind of use possibilities…”

Listen to the podcast: Environmental Love and Care.

The workshop was held from 25 – 27 September 2025 and it was organised in a joint effort between the ASUTUT Sustainable Housing Design research group, Urban Planning research group, Insurgent Spatial Practices research collective, the Head Division of Gender and Globalization studies at Humboldt-University in Berlin, Christine Bauhardt. The lectures and workshops were held in coordination with the courses of Sustainable Architecture, Urban Planning and Design IV, and Housing Design V. The workshop has received funding from the European Union – NextGenerationEU instrument and is funded by the Research Council of Finland under the grant number 353169. The activity was sponsored by STUE-Sustainable Transformation of Urban Environments action grant. STUE is a research community and profiling area in Tampere University.

I would particularly like to thank Jaana Vanhatalo, Jasmin Laitinen, Essi Nisonen, Sofie Pelsmakers for helping to organize this event.

Dalia Milián Bernal is a doctoral researcher, project manager, and teacher in the School of Architecture at the Faculty of the Built Environment. Her research and teaching activities lie at the intersection of architecture, urban planning, and critical urban studies. Through research, she aims to understand the production of space from below and investigate how these, often radical, spatial practices can help illuminate alternative ways to address the multiple but interrelated social, environmental, and climate crises. As a teacher, she aims to position these practices within the curricula of sustainable architecture and planning to offer a more critical, comprehensive, and inclusive understanding of the built environment and to elucidate alternative paths for future architects and planners to engage with in practice for the construction of more just and sustainable living future.