To be honest, the conference’s rather gloomy theme felt like a distant nightmare in affluent Copenhagen when cheerful researchers cruised along Copenhagen’s canals on the pre-conference excursion. With the guidance of local experts, the cruise introduced us to coastal protection and urban development at Amager Beach, the redevelopment of the former industrial port Nordhavn, an artificial island project Lynetteholm, and the transformation of Papirøen from paper warehouses to street food market and luxury housing. These flagship projects, also covered with the mystical veil of sustainability, got us thinking nothing but the challenges of urbanisation: how to align the objective of economic growth, ecological sustainability, and social inclusion.

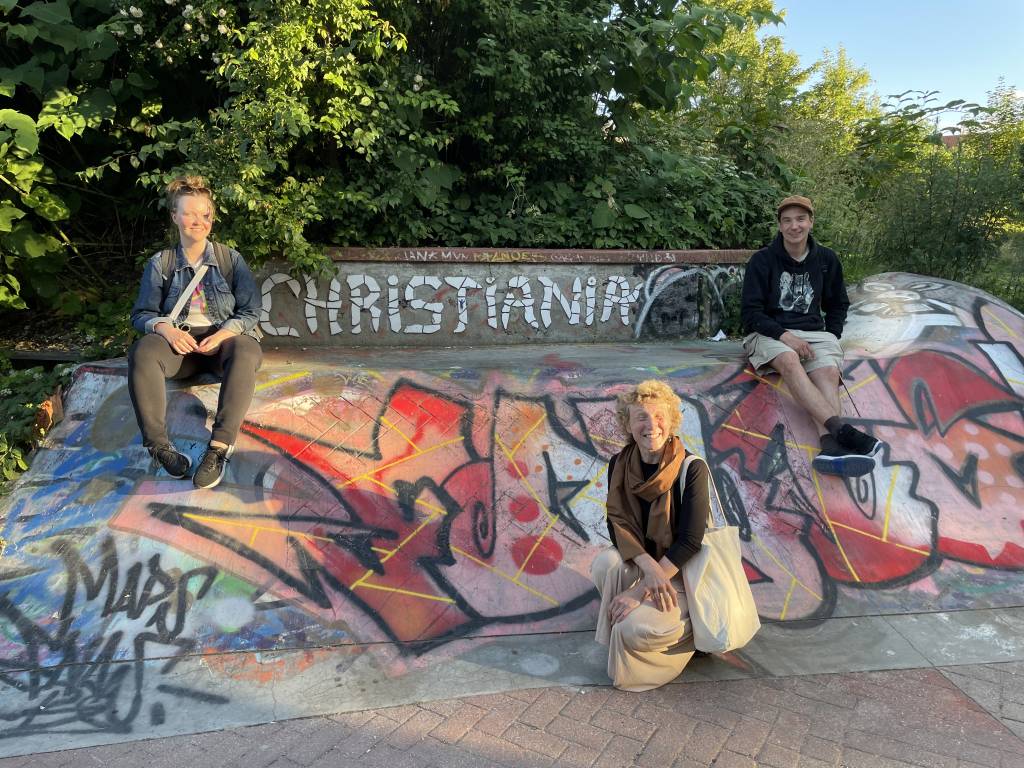

While the excursion got us into the deep end of the socio-spatial transition through the renowned Copenhagen model, Christiania offered another perspective. Despite constant struggles, the former military base has been squatted since 1971 and has somehow survived as an autonomous commune throughout the years. Christiania, which is now a strange mix of hippie utopia and gentrification, is likely to continue to change due to planned housing developments, but also because the main drug market, Pusher Street, was closed, or rather dug up, just a couple of months before our visit.

Wandering around Christiania tuned us nicely into the theme of the session that Antti Wallin and I were ought to organise a few days later: sustainable socio-ecological transition from the bottom-up. We were delighted to share the two-part session “Lessons from bottom-up urbanism for sustainable cities” with enthusiastic researchers whose presentations delved into citizens’ and grassroots organisations’ roles in promoting sustainability and urban development in such diverse cities as Rotterdam, Tampere, Maputo, Blantyre, Lagos, and London.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the knowledge of residents, informal networks, and grassroots organisations proved crucial in organising everyday life in cities with inadequate infrastructure and services. As Onyanta Adama-Ajonye explained, this was the case in Lagos, Nigeria, where the traditional system of market governance, rooted in Yoruba culture, significantly increased the capacity of local governance to respond to the crises. In a similar vein, Ilda Lindell’s presentation of the self-constructed markets in Maputo, Mozambique, and Lennert Jongh’s street vendors in Blantyre, Malawi, illustrated how local traders and associations adopted new practices to reorganise the vital services. All of these cases demonstrated how grassroots social infrastructures have played a critical role in the city’s social regeneration during and after the pandemic.

Local communities, initiatives, and versatile actors shape also the cities of the Global North. Both, Elina Alatalo’s presentation on the collaborative development of the Hiedanranta area in Tampere and Yun Sun’s presentation about the crowdfunded Luchtsingel pedestrian bridge in Rotterdam shed light on how creating new kinds of arenas and practices for citizens to contribute to urban planning can lead to new ideas and solutions that support institutional change and meet the actual physical and social needs.

However, not all citizens’ initiatives support the democratic and participatory dimensions of sustainability transition. Eleanor Jupp offered a critical perspective on community-led gifting and sharing practices involving food, clothing, and household goods in London. Although the initiatives seek to reduce waste and overconsumption, inequality shapes interactions in these spaces in profound and uneasy ways as distributive and social justice are not sufficiently attended to alongside climate concerns.

Sustainability transition is often understood as a systemic change in cities, but it is also the everyday activities of local people that promote ecological and social sustainability. This was brought to light in Krista Willman’s insightful research on urban gardening communities whose work transforms the urban fabric by increasing the amount and qualities of urban green while promoting social encounters, peer learning, and self-sufficient food-growing practices. Based on a forthcoming article, my presentation dealt with urban transformation from the perspective of infrastructure. Hiedanranta and the activities of the skateboarding association Kaarikoirat as a case, I argued that experimenting with urban infrastructure creates the capacity to engender new practices, partnerships, and material ontologies that have wider implications in urban culture and politics of urban development and also in individual’s life journeys.

An ever-topical viewpoint on social sustainability is the role of public space. Antti Wallin’s ongoing research offers an interesting viewpoint on the social dynamics of Kirjastonpuisto public park in Tampere. The park next to the city’s central square is notorious for substance abuse and drinking but it is also a popular skate spot. Antti described how skaters can navigate and mediate socially confusing urban social life, and by this skill, they can make space safer and inclusive for various population groups. In a time of increasing inequality, the case tells an encouraging lesson about sharing urban space despite vast social differences.

Instead of just talking, Antti and I also immersed ourselves in the dynamics of skateboarding and public space. And what would be a better place to skate the best flat ground and ledges while enjoying the spectrum of urban life roll by than the Red Plaza at Superkilen Park in front of the Nørrebrohallen on a sunny evening? Nothing. Whereas Copenhagen is famous for incorporating skateboarding into public spaces, so is Malmö on the other side of Øresund. On our way home, we needed to hit the city’s latest addition to its skateable public spaces, LoveMalmö.

Copenhagen and Malmö are forerunners in integrating skateboarding into urban built environments which has put the cities on every skate tourist’s maps. However, what is to learn from both of these cases and cities more broadly, is not only the emphasis on skateboarding but a profound and nuanced understanding of the essential role of public space as the foundation of urban life – an understanding that is too often lost in technocratic urban planning.

Mikko’s trip to the Nordic Geographers meeting was kindly supported by STUE’s Action Grant.

Mikko Kyrönviita is a researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences, and doctoral researcher in Environmental Policy at the Faculty of Management and Business. He currently works on the Contested Waterfront Transformation project that aims to gain an understanding of the transformation and contestation of social inclusion ideals and traditions of waterfront developments in the age of the financialised urban growth machine. He is also a co-founder of the Insurgent Spatial Practices research collective.