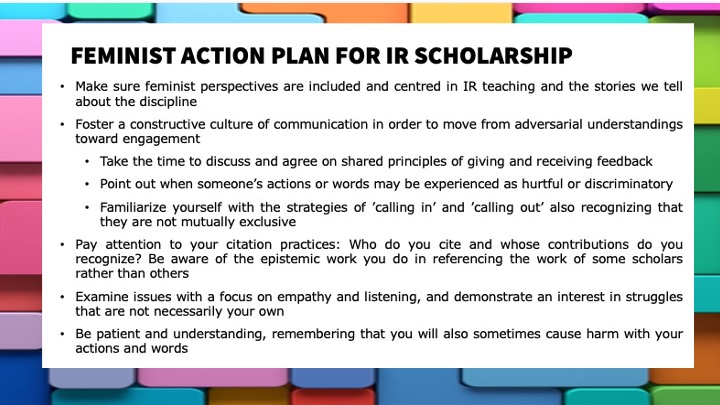

This review of the reading group meeting first summarizes the articles’ main arguments and then continues to think through the discussion they provoked. The action plan (pdf) to stop further marginalizing feminist IR and gender-focused research in the discipline is an outcome of these discussions.

Awkward silences and miscommunications

Although over 20 years apart from each other, both pieces recognized a similar problem; there is a “lack of sustained dialogue” (Tickner 1997, 612) between feminist theorizations and the discipline’s mainstream. Worse still, the “cooptation and trivialization” of research centred on gender in IR takes place to this day (Sjoberg and Thies, 452–453).

The article “You Just Don’t Understand” sets out to build bridges between feminist theorizing and the mainstream approaches in IR. As mentioned, the starting point to the argument is that there are “awkward silences”, “lack of sustained dialogue” and “miscommunications” when it comes to feminist International Relations research (Tickner 1997).

Is the personal international? Are feminists really ‘doing’ ir?

One of the main arguments Ticker makes, we discussed, is that “contemporary feminist perspectives on international relations are based on ontologies and epistemologies that are quite different from those that inform the conventional discipline” (ibid.). More specifically, Tickner argues that the academic community has misunderstood the logic of the feminist perspective. To address the myriad miscommunications, Tickner details a set of misunderstanding about feminist work common in the field (ibid., 613). These are then tackled by answering three questions often levelled against Tickner and her colleagues: “[I]s the personal international?” (ibid., 614), “are the feminists really ‘doing’ ir?” (ibid., 615), and “where is your research program?” (ibid., 617).

When it comes to gender, Tickner asserts that “Feminist scholars claim that gender differences permeate all facets of public and private life” (ibid., 614) and, thus, gender is intimately linked to questions of ‘the international’. As for whether feminist perspectives can be considered ‘proper’ IR, Tickner points to the different ontological understandings of what IR is to feminist writers.

First, the focus of feminist perspectives has centred on individuals “rather than on decontextualized unitary states and anarchical international structures” (ibid., 616). Second, feminist perspectives have shone a light on and challenged the “gendered biases” of “the Western philosophical tradition” (ibid., 617) which has also contributed to a fundamentally different ontological understanding of what IR is. Lastly, answering the epistemological question of whether feminist IR is ‘good science’, Tickner points to – on the one hand – “epistemological pluralism” common to feminist approaches (ibid., 619). On the other hand, Tickner also points to the way that the mainstream approaches favouring positivist ways of understanding and doing social sciences ultimately end up restricting what kind of questions and answers there can be (ibid., 622).

Power inequalities allow the mainstream to ignore feminist IR while feminists also need to keep up with the mainstream

Thus, feminist perspectives and Tickner’s argumentation point to how politics and power are entangled in knowledge-producing practices. As she eloquently puts it: “Inequalities in power between mainstream and feminist IR allow for greater ignorance of feminist approaches on the part of the mainstream than is possible for feminists with respect to conventional IR, if they are to be accorded any legitimacy within the profession” (ibid., 629).

The article “Gender and International Relations” by Laura Sjoberg and Cameron Thies (2023) offers an overview of recent trends in analyzing gender in International Relations. Four research areas and examples from each of them are presented to highlight the diversity and pluralism of gender-focused approaches to doing IR. The different research interests and (loosely defined) research communities include (1) gender and the global political economy, (2) gender and security, (3) queer IR, and (4) feminist foreign policy.

In the reading group, we discussed how the article feels and reads like a literature review, taking stock of what is going on and topical in researching gender in IR. Rather than calling for a top-down or unified research agenda, Sjoberg and Thies (2023, 460) make a case for pluralism (similar to Tickner). Also, the authors point note that “[g]ender and IR work is more and more international, more and more intersectional, and more and more decolonial” (ibid. 461). We contended that the intersectional and decolonial aspects are the biggest thing to set this article apart from the Tickner piece which does not thoroughly engage with those conversations.

Reflections on situatedness and vulnerabilities

The two articles ignited a lively conversation about feminist IR among the reading group participants. It should also be noted that it is not possible to exhaustively summarize the thoughts and feelings that came up in the meeting. The format of writing limits some of the aspects of the discussion from the start. Having said this, we did think that this is an important topic to discuss and dive into even if it feels difficult or awkward when our own situatedness and vulnerabilities are so entangled with the issue. One of the reading group members argued that as a ‘white dude doing security’ it is difficult to comment on feminist work if one wants to avoid taking part in gatekeeping. Being acutely aware of the power relations within academia when it comes to gender and race, he commented that he — as someone perceived as a part of the ruling establishment — has not found a way to comment on feminist IR theory without feeling that it is not his place to do so.

As a ‘white dude doing security’ it is not always easy to comment on feminist work

One of the big topics the two readings provoked was the question of doing feminist IR in Finland and being ‘labelled’ as a feminist IR researcher. There were differing experiences as to how feminist IR has been presented to us in the first place. Some felt that during their studies it was implicitly dismissed as something less scientific and legitimate whereas others felt that it had, at least at some point,been presented as a promising line of research – curiously, however, mainly for gender-conforming female students.

We also discussed the Finnish International Studies Association’s 2022 conference panel which focused on the silences in IR, specifically on how people doing feminist IR have been arguably stunted in their careers in Finnish Politics departments. We agreed that doing feminist IR should not be a possible hindrance to career development in 2023 but that, in reality, some of us still fear and feel that it might be. It seems that institutional change in this regard is slow and that the people in the gate-keeping positions are not fully aware of their power in this equation.

Second, the question of citation practices and citation ethics came up. Many of us felt that the Tickner piece, for example, felt somewhat outdated in that many of the feminist perspectives seemed taken-for-granted and obvious to readers in 2023. Having said this, we also acknowledged how the problem of cooptation of feminist perspectives into more mainstream research without crediting the original sources. We are expected to know and care about the big names in the field in a way that we are not expected to credit and reference the classics of feminist IR, not to mention the more marginal authors.

The readings and the discussion made us more aware of our own complicity in who gets to be seen and heard in the discipline

We also discussed how the list of references in the article by Sjoberg and Thies is very Anglocentric although the article critically talks about feminism’s troubled relationship with coloniality. The two readings and the ensuing discussion made us more aware of our own complicity in who gets to be seen and heard in the discipline.

Third, we contemplated on the issue of essentializing. Both readings problematize the universalizing logic of the discipline’s mainstream. Yet, we discussed that to a certain degree, both readings might themselves perpetuate a specific essentializing logic even while they emphasize that feminist IR is not only about women but more broadly about gender and gendering. A call for pluralism is present in both Tickner (1997) and Sjoberg & Thies (2023) but – at the same time – the role of gender and the position of women are heavily centered. This, we believe, runs the risk of constructing the focus on gender as an essentializing move. One of our reading group members mentioned that the plea for pluralism felt slightly disingenuous for them when (if?) the key point of feminist IR is that gender relations override the dynamics that other subfields of IR are interested in.

A call for pluralism also invites critical reflection on the Anglocentrity of the discipline and the idea of centering the role of gender in IR

That said, we equally discussed how forgetting the dimensions of gender altogether in research works as a gender-blind and silencing tactic. All in all, during our meeting, in line with feminist theorizing, we became acutely aware of our positionality and situatedness in the discipline and its real-life effects. Thus, throughout our conversation, we were somewhat gripped by what we could do. The action plan presented above is suggested as a starting point.

References

Sjoberg, Laura & Thies, Cameron G. (2023): Gender and International Relations. Annual Review of Political Science, 26(1), 451–467. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-110954https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2478.00060

Tickner, J. Ann (1997): You Just Don’t Understand: Troubled Engagements between Feminists and IR Theorists. International Studies Quarterly, 41(4), 611–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2478.00060

The Feminist Action Plan has been inspired by the following sources, for example

Harvard University (nd) Calling In and Calling Out Guide. https://edib.harvard.edu/calling-and-calling-out-guide

Phipps, Alison (nd) Principles for a Feminist Classroom. https://genderate.files.wordpress.com/2022/01/ma-gender-studies-classroom-principles.png

The images on these pages have been generated with the help of AI tools