In small groups, we first identified challenges we had come across during the week, then picked one of them, and started to narrow it down and develop solutions to the problem. It was a typical way of having a hackathon, and we finished by presenting our solutions for others. What made this hackathon special were the amazingly beautiful milieu of Kylemore Abbey, and the experts and stakeholders we had met during the week who also participated in the hackathon and were willing to discuss and answer our questions.

Getting started: Identifying the problem

After learning about many different issues throughout the week, deciding on one problem to focus on was surprisingly easy. During the field course, we visited Lough Carra, which is one of the finest examples of a marl lake habitat in the whole Europe. The lake and its catchment area offer important limestone and wetland habitats for multiple key species. At the lake, we were given presentations about Lough Carra LIFE -project that aims to restore the habitat by working with the local community. Inspired by the visit, we picked Lough Carra and its threatened biodiversity as our problem. To narrow the scope of it, we identified two main causes for biodiversity loss, eutrophication and invasive species, and decided to focus on the first one. More specifically, we focused on the nutrient run-off caused mainly by agriculture, as that is a major reason for eutrophication.

To understand the problem, as well as its causes and impacts, we made a problem tree. All the SUD students probably knew it well at this point of spring and Urban lab course, but this time, a student from another programme suggested it first. I was happy to notice that having properly learnt the method beforehand came in useful in the hackathon.

Going forward: developing solutions

At the end of our attempt to identify the problems, we had two most prominent ones in mind. First, the current legislation to fight nutrient run-off is not enforced to be applied in practice, and second, some of the existing policies discourage combatting run-off instead of incentivising it. In the Lough Carra catchment area, there is a lot of agricultural land owned by farmers. Therefore, it is essential to encourage and support the farmers to make changes and protect the lake. Hence, in our proposals we focused on changing policies and incentives to support and encourage farmers to protect Lough Carra and change their practises to be more sustainable.

Solution 1: Buffer zones

Buffer zones, or buffer strips, are pieces of land with permanent vegetation that separate water from agricultural land. In the case of Lough Carra’s catchment area, buffer zones could mean having vegetation, and perhaps also a fence, in between the lake and the area where cattle and sheep graze. Buffer zones filter out soil particles that contain phosphor, nitrate, and other nutrients, and that is why they are efficient in fighting eutrophication. In addition, they can offer a living habitat for insects, for example, and support biodiversity in this way too. However, the current policies, such as EU’s common agricultural policy, do not encourage farmers to create buffer zones, as the farmers do not get monetary benefits for creating them. On the contrary, it is unprofitable, as the farmers get the benefits based on the area that they are farming on, and buffer zones would decrease that. Therefore, giving up some of that area for buffer zones causes losses in the farmers’ income. We concluded that the common agricultural policy must be changed, so that it rewards farmers for implementing buffer zones instead of punishing them. To combine carrot and stick approaches, there should also be a law that requires having buffer zone around the lake.

Solution 2: Reducing the number of livestock

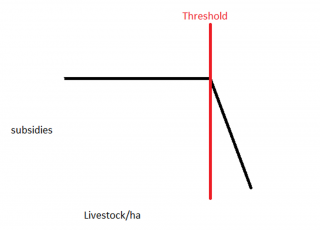

Complementary to the first solution, our group thought that reducing the livestock in the area would be an effective, yet not so popular option for reducing the nutrient run-off. Thinking about how to get everyone, most importantly the farmers, to favour this idea, we tried to figure out how to make it profitable for them. As a result, we proposed that the subsides related to animal agriculture should be changed: instead of the subsides being tied to number of livestock, the amount should stay the same until a threshold of a certain number of livestock. After that threshold, the amount of subsides would drastically start to decrease. In other words, the subsidy per one animal would have to be higher for farmers to make their living, but having more animals would not make the business more profitable. This would eventually reduce the number of livestock in the area without compromising the livelihoods of local farmers.

Finishing with applause: presenting and discussing

The hackathon ended with each group presenting their solutions. The aim was to have a five-minute pitch during which the audience would be convinced of our ideas. Only two members of each group were allowed to present, to keep it efficient. Even though it was a little bit unnerving situation, and the presentation did not go as smoothly as I had wished, I could not have imagined a better audience. During the week, we had had time to get to know one another, and I knew everyone was friendly and interested in the topics. Hence, it didn’t bother me too much to struggle with difficult words, but I took it as a great opportunity to practise my presentation skills. At the end, we got a couple of tough questions, such as how to make sure that farmers are included in the change. That is an especially relevant question, as in Ireland, most of the land is privately owned, and farmers make a significant proportion of the owners. Therefore, making any changes to preserve biodiversity is not possible without getting farmers on board, which is exactly why we targeted our policy suggestions to encourage farmers to take part in the conservation of biodiversity.

At the end of the sunny day in Kylemore Abbey, I was astonished by the quality of each group’s work. The hackathon was like a fast-phased version of our Urban lab course. Of course, we had already been engaging with the area and its issues throughout the week, but in the hackathon, we investigated the topics deeper by identifying problems and proposing solutions, and already took action by pitching our ideas. It differed from the Urban lab in that it was all done in one day instead of a semester. Thinking about it now, it was a combination of good groupwork- and problem-solving skills and the all the expertise present that made the day so successful. We had students from different countries and study programs with diverse sets of knowledge and skills, as well as multiple experts and teachers who helped us to shape our solutions. In conclusion, multidisciplinary work showed its strengths in the hackathon. After the hackathon, I understand better what it means that solving sustainability issues requires not only knowledge and expertise but also soft skills, such as all the skills and methods related to problem-solving and keeping up a motivating atmosphere in a group – without these, all the knowledge could never be applied in practice.

Veera Uusitalo

Veera participated in the Erasmus+ field trip to the West of Ireland in April 2023. The trip was organized by Dublin City University in collaboration with Tampere University and Utrecht University.