Children washed ashore on the coasts of Turkey and elsewhere; refugees1 being detained in the hotspots on the Mediterranean islands, waiting either to be returned or their asylum applications to be processed; and thousands of migrants walking thousands of kilometers to reach Germany in the summer of 2015… Those are the costs of fleeing from home, where there is an ongoing civil war for years; fleeing with the hope for a better life, with human rights and dignity. And those are the incidents happened in the 21st century, in front of the eyes of the millions, which turned out to be “one of the largest forced movements of people since the end of World War II” as described by scholars and the media.

Being close to the conflict regions, Middle East and North Africa, and offering better life conditions than elsewhere closer, the EU has become the ideal destination for refugees. Yet, the response to the crisis has been tardy as no one was anticipating such an immense humanitarian crisis. In the meantime, with the purpose of better responding to the “migratory flows” and “creating a fairer, more efficient and more sustainable system for allocating asylum applications among Member States,”2 the EU began to seek for reforming the Common European Asylum System (CEAS).

System of a Down: The Lack of Solidarity and Burden-sharing

The Syrian civil war and the events occurred afterwards in the Eastern Mediterranean route have been the stimuli for the EU that the status quo asylum system was no longer functioning: several Member States (MS) suspended the implementation of the Dublin system, which is considered as the core of CEAS, in order to host refugees arriving in their territories; while some other MS such as Hungary strengthened their national borders; and the EU sought to tackle the issue by resorting to externalization, merely outsourcing the responsibility, rather than finding feasible internal solutions that meet the international standards of refugee law.

In this respect, the most concrete evidence of such externalization attempt has resulted in the so-called EU-Turkey statement of 18 March 2016, of which the legality is still contested. Refugees are merely used as a bargaining tool: in exchange for Turkey to receive €6 million, a promise for visa liberalization, revision of the Customs Union, and acceleration of the accession process to the EU; and for the EU to create a buffer zone at its external borders while making Turkey a gatekeeper to host more than 3 million refugees.3

According to the Article 33(1) of the Geneva Convention, the principle of non-refoulement prohibits contracting states to expel or return refugees in any manner to the countries where their life or freedom would be threatened. While designating Turkey as a “safe third country” under the Asylum Procedures Directive,4 to which the migrants can be returned without a further investigation, there is no doubt that such agreement contradicts with the principle of non-refoulement since the political and human rights situation in Turkey is very unstable and contested.

Change Happens? Dublin IV Regulation and Beyond

As the “massive influxes” have come to a halt, especially after the EU-Turkey statement, the crisis was put on hold in the short term. Meanwhile, the EU put forward proposals to reform its asylum system. Indeed, refugees, who have been the victims of restrictive and externalized measures implemented by the EU, began to shape the policy-making process: driving the EU to adopt a more efficient asylum policy to better respond to the needs of asylum-seekers. In this regard, their agency is undeniable.

With the proposals for regulating Dublin system, which forms the basis of CEAS, as well as for reforming the Directives of CEAS regarding asylum procedure and qualification, and reception centers,5 heated debates appeared at the EU level. Overall, the proposal by the Commission for the revision of Dublin III Regulation, which sets out the criteria and mechanisms allocating responsibility between MS for asylum applications, further tightens the asylum procedure.

Accordingly,6 the MS of first entry will remain responsible in applications lodged by asylum-seekers, including by unaccompanied minors, and in examining whether they are coming from a safe country of origin or a safe third country. And any relocation process cannot be applicable if they are found to have come so. The scope of the appeals against such decisions are also limited, which certainly contradicts with the right to an effective remedy.

Moreover, the proposal transforming the existing European Asylum Support Office (EASO) into a fully-fledged European Union Agency for Asylum will bring further institutionalization. Meanwhile, the Council adopted further measures for the reinforcement of controls at external borders, and launched the European Border and Coast Guard Agency.7

Unlike the purpose of promoting “solidarity” and “responsibility sharing” stated by the Parliament,8 the CEAS reform inter alia reinforces the external borders of the EU and disregards the obligation of providing effective protection. As first Vice-President of the Commission, Frans Timmermans said, “managing migration better requires action on several fronts, to manage our external borders more effectively, cooperate better with third countries, put an end to smuggling and resettle refugees directly to the EU,”9 the EU still needs to think out of the box: respecting the rights of refugees, and going beyond the practices of controlling external borders, of shifting the burden to third countries, and of perceiving forced migration as a security issue.

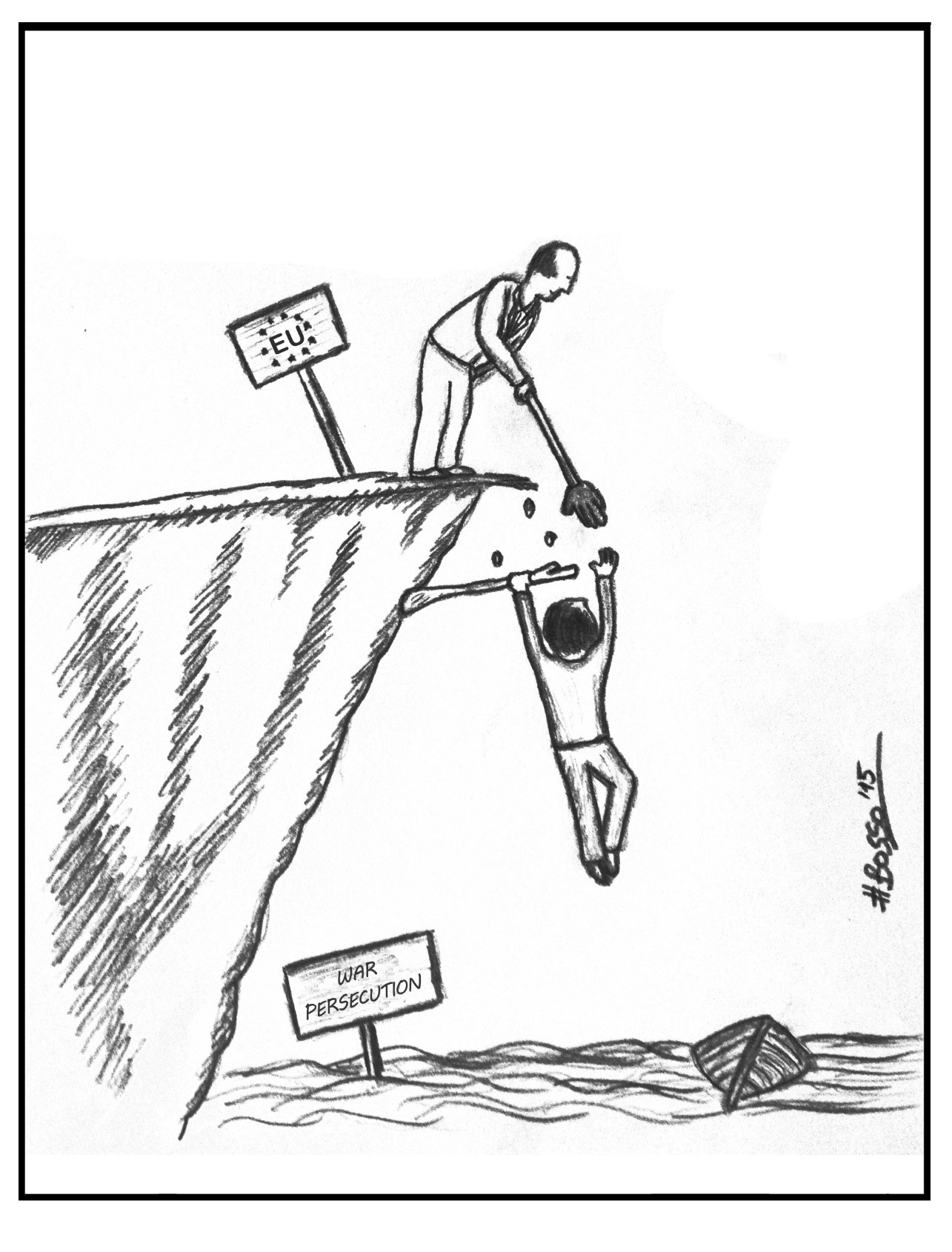

Caricature by the author

About the Author

Berfin Nur Osso is a Master’s Degree student in Leadership for Change at the University of Tampere, with a specialization in Politics. She obtained her Bachelor’s Degree in Law, with a minor in International Relations, from Koç University, Istanbul. Her research interests are human rights law, international refugee law, and the EU policy on asylum. She loves to harmonize caricature with law and politics.

1In the article, the term “refugee” is used for refugees, asylum-seekers and forced migrants.

2European Commission (2016, May 4). Towards a sustainable and fair Common European Asylum System [Press release].

3According to UNHCR, total number of the persons of concern with regard to refugees registered in Turkey is 3,547,194 as of March 2018. See: UNHCR (2018). Syria Regional Refugee Response: Turkey.

4European Parliament and European Council (2013). Directive on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection (“Asylum Procedures Directive”) (2013/32/EU). Brussels: European Parliament, 26.6.2013.

5European Parliament (2018, February 20). TOWARDS A NEW POLICY ON MIGRATION: REFORM OF THE COMMON EUROPEAN ASYLUM SYSTEM.

6European Commission (2016). Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national or a stateless person (recast) (COM(2016) 270 final). Brussels: European Commission.

7European Council (2017). Strengthening the EU’s external borders.

8European Parliament (2018, February 20)

9European Commission (2016, May 4)

Kommentit