In this blog post we take a quick look at what has been accomplished in the work package 2, which centers around the programming of mixed fleet systems. In addition, future goals are also examined. The post is divided in the two sections: in the first section we examine at how large language models can be utilized to create robotic plans while the second section describes a model-based-approach to mixed fleet programming.

Creating robot action using large language models

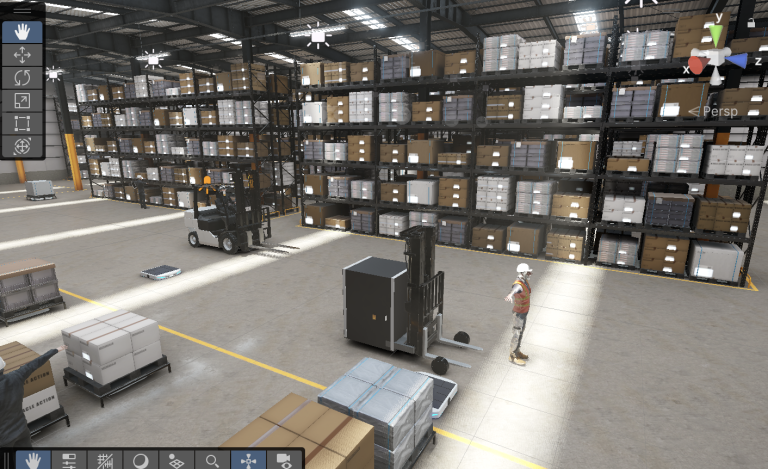

In the last few years, the popularity and utilization of large language models has risen rapidly with the emergence of tools such as ChatGPT. Subsequently, the mixed fleet project is no exception. For the past few months, the focus in this area has been on developing a simulation environment for robots that aims to demonstrate the ability of large language models to generate robotic actions plans based on user input. A secondary goal is to provide a reusable simulation platform to be used in other parts of the project, especially as a demonstration platform for the model-based approach that you can read more about below. The simulation is based on two open-sourced projects: Robot Operating System 2 (ROS2) and Gazebo Sim. The former provides tools for developing the functionality of the robot while the latter provides the simulation environment.

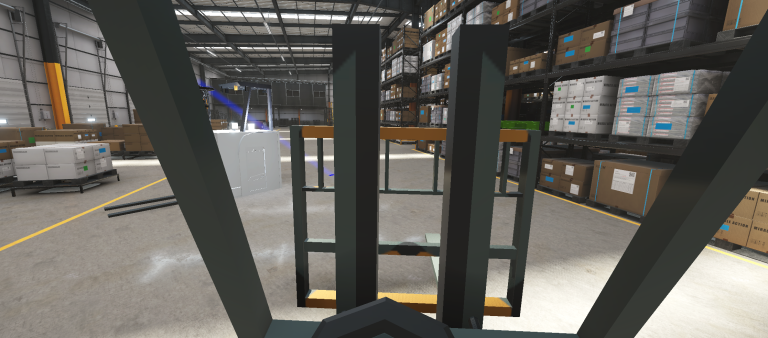

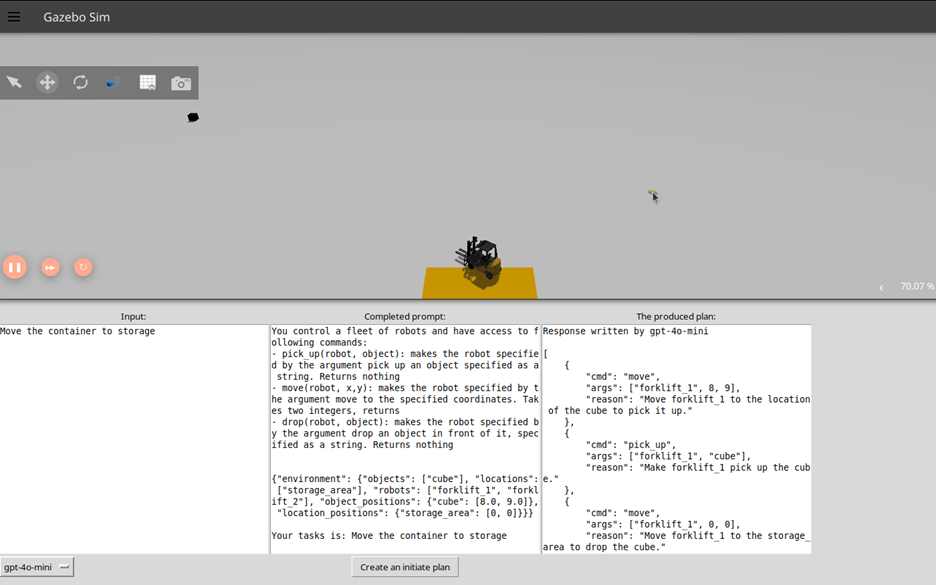

At the moment, the developed platform supports the control of multiple forklift robots which can move, pick up and drop objects in the world. The user may input a high-level goal for the robot(s) in a natural language through a graphical user interface. One such goal could be moving an object from one position to another. A language model such as GPT-4, Llama or Claude receives this prompt and constructs an appropriate action plan to achieve the given goal. This plan is then executed in the simulation. To achieve this, the language model is given information about the environment, actions available to the robot, the goal itself and possibly other instructions about things such as formatting. For this implementation, I chose to use JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) which is user-friendly and a widely used file format, especially in web applications. Below I give an example what a prompt given to a language model could look like:

| Prompt component | Contents |

| User given task | This part contains a task given by the end user, for example picking up a container |

| Robot role and skills | Role for the robot, (for example forklift) and the skills such as picking up, moving and lowering the fork. |

| Environment description | All the details that can affect the mission and are related to the operation environment such details about the objects and locations (like coordinates) |

| Formatting instructions | This contains specific instructions regarding the answer format. For example: “Return your answer as a text” or “Give your answer in JSON format” |

| PROMPT = User given task + robot role and skills + environment description + formatting instructions | |

Automatic generation of the prompt “behind the scenes” ensures that the end-user does not have to know anything about the internal implementation of the robots or their behavior. All the end users must do is give a task for the robot. A complete view of the environment can be seen in the image below: The upper window is the simulation environment while the bottom window is the user interface the end-user uses to give tasks to the robot. The GUI has three columns: one for input, one for showing the prompt that is sent to the language model, and the third column shows the generated plan for the robot:

So far, large language models have shown to be capable of generating robotic action plans successfully from simple user-given input. The next steps for research will include additional verification of the produced plans, creation of a more complex simulation environment and additional capabilities for replanning in cases where a task is not completed successfully.

Exploring model-based approaches

While natural language programming offers an intuitive way for experts to describe tasks, there’s another approach that takes a slightly different path to the same goal of empowering domain experts to program those mobile machines through model-based engineering.

The aim through model-driven engineering (MBE) is to unable domain experts to use structured, graphical or textual models to represent system behavior by defining outcomes and computer takes care of generating the code to achieve those outcomes by following a strictly deterministic and reliable process this is supposed to ensure precision, reusability and reduce resilience in AI interpretation (with its challenges of trustworthiness) that exists in natural language programming.

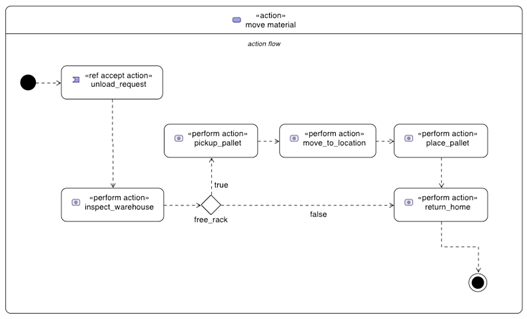

To illustrate the system’s behavior and interactions, we created a graphical SysML action flow. This flow visually represents how various components like drones and forklifts collaborate to achieve moving materials task in a warehouse.

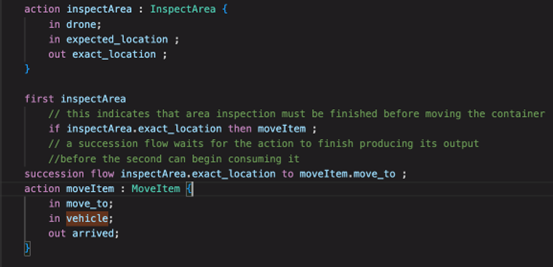

A textual approach can be used also, in the next example we used it to achieve a material handling task where the drone inspects a location to determine the exact coordinates of an available spot, and the output of this inspection task drives the subsequent MoveItem action that involves a forklift moving to the identified location and completing the task. At this textual notation example, we included conditional logic, binding inputs and outputs between actions to ensure seamless data flow. With this modular and structured textual representation, the process is not only clear and accurate but also easy to maintain comparing to the graphical approach.

Both approaches can be used by domain experts each bringing advantages and challenges. The coming days will provide valuable insights into how can we create systems that are not only robust and reliable but also highly adaptable to the needs of domain experts, which approach is more suitable toward this goal, or model-based engineering and natural language programming can be combined to get the best of both?

Written by Elmeri Pohjois-Koivisto and Hamza Haoui